Sunday, August 13, 2017

The Surgeon's Dilemma

She may either take out the brain of someone and so demonstrate that this individual will no longer think,

or,

she may not take it out and the person will still think that the mind is the ghost in the machine.

Either she will demonstrate that an individual needs the brain to think and it will kill the person or she will not demonstrate it and the person will live.

What is right and what is wrong with this dilemma?

Sunday, May 7, 2017

Philosophy, Religion, and Science

Philosophy is not Religion, Religion is not Science, and Science is not Philosophy.

Thursday, April 6, 2017

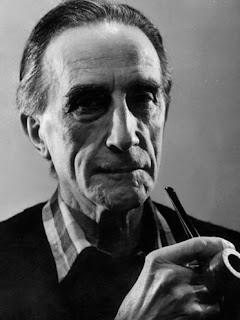

Marcel Duchamp and the Ethics of Empathy

|

| Marcel Duchamp, 1887-1968 |

This is where Duchamp comes into the discussion. He stated a variation on the Golden Rule and revised it as “Do unto others as they wish, but with imagination.” The creative employment of ethics is something rarely discussed, but to do it imaginatively may be uniquely human.

Wednesday, March 8, 2017

Darwin and the Golden Rule

Tuesday, March 7, 2017

The Euthyphro Dilemma...Still Going Strong After 2500 Years

I think this

is always a good question to ask religious followers, including myself: is an

act right because the gods say it is so, or is it right because it is right in

itself? This does make a person pursue

the inquiry further.

If one says that there is no need to justify the command because the divinity is good, then one has to figure out how to justify whether the divinity is good.

All it does is push the question back one more step.

If another claims that there is rational justification for the command as good, then one could ground it in the rational justification and there would be no need for the command.

The underlying theme here, however, is one of responsibility. Did Euthyphro own up to his actions or did he fall back on how he understood the godly guide?

Most Middle East monotheist apologists emphasize that the dilemma is a false dichotomy,

and insofar as any dilemma may be a false dichotomy then that may be the

case. But, then again, it does not remove the dilemma entirely for the logic presented previously.

Long ago in an

on-campus classroom, I remember one student pointed out that if the gods are

intrinsically good then if they say something is so then one can presume

reasonably that it is also good.

As it turns out, this is the position of most Jewish or Christian apologists; i.e., the divinity would not command what is bad since their gods do not change; i.e., they would not be led by caprice. But what is the evidence for that beyond apologetic assertion?

Anyway, I thought the problem was that it also means that one

has to determine if the gods are good regardless of the divine

recommendation. And how does one do that?

This student

also noted that maybe human beings need the divine recommendation so they know what is good. That is something to consider too but then the

problem becomes how is one sure that the recommendation is good or divine etc.

Later,

an individual wrote to me claiming that monotheism takes care of the problem since,

then, there are no gods or no competition among them.

At

first, that might be the case but then we still have the problem that we have

to decide what the One Deity commands is good.

And

while we do away with the burden of competition among gods and their various

commands, we still need to consider the change over time.

For

those following a Western religion the issue is one of a change over

time. Why was it good to command families to stone a rebellious child

(Deut. 13, 21) and now very few people—Jews as well as Christians--would agree

to that?

A

Christian might say because now we are in the New Covenant it is different, but

nothing in the NT speaks to this directly (though from the Sermon on the Mount

one might infer that it would be unacceptable).

Another Christian may claim that Jesus fulfilled the OT prophecies in his advent as the Messiah.

That's fine, but how is that relevant to particular commands of behavior?

A

Jewish person might say that until the Temple is restored one cannot live by

all 613 mitzvot (“commandments”), but does this mean that such a command would

be good then?

And

even in one covenant there are changes. One example is Passover.

There are six, if not more, changes from Exodus to Deuteronomy as to how the

Israelites were to observe it regarding the place, the food, the cooking

method, when to offer it, whether it was separate from the feast of unleavened

bread, and the participants.

What was good for Passover in Exodus apparently was not good for Passover in Deuteronomy. Naturally, one gives leeway to development in any religion as well as understanding that the religious community will work out a solution to this.

To the proverbial Man from Mars, however, it does appear that there has been a change.

The

Euthyphro dilemma is still a weighty problem for any religious follower.

Monday, February 27, 2017

Brief Notes: The Enlightenment and Its Legacy

The Enlightenment period really had quite an effect on the world that is still felt today. Some may think it’s good and others may think it’s bad. I would say that it’s been good, on the whole. I think that it has affected people through both politics and scientific fields, to be sure.

Not that I think that it was all so good, there were some flaws. Perhaps setting up Reason as a sort of idol, though this certainly was not the intention, may have altered the notion that Reason is a tool more than a source of goodness (or of badness, for that matter).

We may be the heirs—and bankrupt heirs—of the Enlightenment. Looking at the current climate today with so much pseudo-science and proto-logical thinking being used by people to manipulate others, I wonder if the Enlightenment was just a blip on the screen of human history?

To state that variant ideas and cultural customs are more idiosyncratic than inherent is quite a radical approach to anthropology. If true, this would mean that people can cooperate and do things without much conflict.

Today, I think that we have to be careful about imposing our world-view on others (and, ironically, this means an Enlightenment attitude to the world), but seeing people as rational individuals capable of doing things together—I would think this is a positive feature of Enlightenment thinking.